Alec Soth, Dayanita Singh, Tom Hunter, Takashi Homma and Vanessa Winship choose new names to watch from an artist whos ripping female portraiture apart, to a Japanese observer of German society and a slum-dweller turned Delhi archivist

Katie Bret Day, chosen by Tom Hunter

Its a publishers idea of hell, laughs Tom Hunter, the renowned British artist-photographer best known for his staged tableaux referencing old master paintings. Hes talking about Lacuna, an extraordinary new photography book by 25-year-old Londoner Katie Bret Day. Usually, photographers try to make books as cheaply as possible, as many as possible, then get rid of them and make a profit. Whereas shes hand-stitching all these things together, hand-printing every picture. When you pick it up, youre really intrigued by it: what is this? It breaks all the conventions. It sets up a whole new language.

Bret Day brings along a copy of Lacuna one of just 50 when we meet at a cafe in Hackney. Its a busy week for her. Shes getting ready for a show at Photofusion gallery in Brixton, south London, her biggest to date, and has recently got back from Switzerland, where she was artist-in-residence at the Institut Le Rosey for a year. Meanwhile, shes about to start a photography MA at the Royal College of Art, continuing a fascination that began when she first picked up a camera at the age of 10.

Man Ray is the obvious one, she says when I ask about her influences. He was one of the triggers for me getting into the darkroom and thinking: this is so cool, its way more than just clicking the shutter. The darkroom remains a central part of Bret Days practice shes fascinated by what happens when traditional printing methods are brought to bear on photographs that are taken digitally. Much of this she does at home, with basic developing kit and a blackout blind. I really like being able to have an idea and execute it immediately, she says. And also not having to go out and spend a fortune.

Hunter, who taught Bret Day at London College of Communication, is impressed by her approach. Katies part of that generation thats bored of Photoshop, that wants to get their hands dirty and really explore the medium for themselves, not just touching buttons on a screen, he says.

Lacuna has taken her more than a year to put together and, flicking through it, I begin to appreciate why. This is no straightforward collection of photographs: the materiality of the text is just as important as the images. The first thing you notice is the variety of surfaces Bret Day has used, including tracing-paper, mirrors and sheets of acetate, which can be lifted to reveal a variant image underneath.

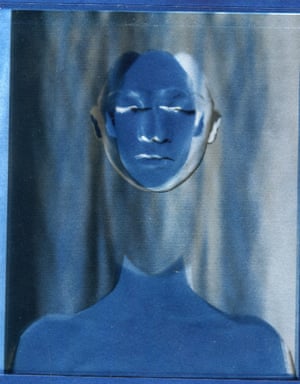

On one page, a partial image of a face Bret Days own is meshed with thick scar-like lines, as if the photograph has been torn up and reassembled to accentuate the ruptures. This is printed on an emulsion-coated acetate with watercolours added on top, she says. The lines across the face could be seen as a net, conveying an idea of entrapment a recurring theme in the book or, Bret Day suggests, you could view them as human cells, a reminder of how were made up of many different things.

Shes fascinated by human physicality, and her photographs have a visceral quality that can be quite unsettling. When it came to shooting Lacuna, which is full of disembodied heads and headless torsos, she used the closest model to hand: herself. At university, I became aware of what it means to be photographing other women and what it means to be a woman photographer, she says. By using myself, Im trying to gain complete control of that gaze, that body, that image. It strengthens my voice.

Shes exploring her sexuality and body image but shes doing it for the female gaze, says Hunter. Shes not letting men tell her how to present herself. Some of the pictures are incredibly beautiful, almost sexual, but at the same time theyre really disturbing. Shes ripping the sugary gloss off female portraiture. Killian Fox

Interventions & Interruptions, a group show featuring work by Katie Bret Day, is at Photofusion, London until 16 Nov

Mayank Austen Soofi, chosen by Dayanita Singh

Even Mayank Austen Soofis name is an art work, enthuses the acclaimed photographer Dayanita Singh, as she praises the 38-year-old photographer/writer (aka thedelhiwalla) who has made Delhi his subject on Instagram his sympathetic, witty posts (topping 20,000) as regular as daily bread. Ask him about his name, she urges.

Mayank means moon in Sanskrit, he begins. It is the name my parents gave me.

His childhood was privileged, his father a government engineer who worked all over Uttar Pradesh. Everyone in his family proved engineer material except Mayank himself (who still wakes in a sweat dreaming of maths lessons). Rebelling against his familys expectations, he found work as a waiter at the Radisson Blu in Delhi and lived in a slum behind the hotel. That was 12 years ago, and a desperate time he was close to suicidal.

But then, in 2007, Mayank started a blog: his first picture was of a funeral procession from old Delhi to a new part of the city in mid-winter. It was a moment in which nothing happened, yet so many things did. He was very moved to witness the final journey of a stranger, and caught the horse-driven cortege on camera. Taking photographs is like reading, he says: you see the story.

Austen, the second part of his name, is a homage: because of my love for Jane. Literature, he says, saved saves him: Books give you joy and oxygen. Other literary idols include Emily Dickinson and Marcel Proust. But it is to a living novelist, Arundhati Roy, that he is most indebted his cover photo for her bestseller The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, of a white marble grave with faded rose and dead fly as ornaments, was his first conspicuous coup. The day we speak, he is celebrating the appearance of his portrait of Arundhati Roy on her next book, My Seditious Heart.

Singh best known for her beautiful photo-books exploring the poetic possibilities of sequencing makes huge claims for Soofi, believing he is redefining photography itself: He is blurring the lines of what we think of as a photograph more than he realises. He is Delhis self-appointed archivist.

Every day he takes numerous photographs images of every section of society on his iPhone8 Plus and often uploads them directly onto Instagram with captions. Today, his pictures include a man sleeping on his hands and on his flip-flops; a ragged, flowery sofa he playfully suggests might have belonged to Emily Dickinson; a little Indian girl, pensively grooming a Barbie doll, captioned Her Experiments with the Caucasian World. As Singh observes: You never feel he is sneaking up on people; there is always a connection. What makes him original is, in part, that his hyperlocal narrative is ongoing, unending. It is missing the point, Singh argues, to single out particular works to praise.

Soofis work is characterised by such affectionate, humorous solidarity that it comes as a surprise when he declares Delhi to be a terrible city. I walk in the early morning and late into the night. You pass through many continents in a single day, you see all aspects of the street and its inequalities. As we discuss one image, The Hawker of Other Peoples Happiness, of a street trader standing stoically with a bicycle loaded with hessian bags and a handful of red, yellow and lime-green helium balloons above his head, he says the city is full of people who do not choose what they do.

Soofi himself is not among their number. Every day, he writes a story about Delhi for Hindustan Times (I dont know who gets space like this! Singh exclaims). He worries that the stories might dry up, but they never do. Nor does he: his engaged, engaging torrent of talk is as beguiling as his writing. He is not ambitious, yet when the server for his blog temporarily crashed, in 2015, he found it tragic, like losing a close friend.

He enjoys Delhis literary mafia, comparing its bitchy gossip to a Proustian salon, but remains apart from it. He is, Singh implies, an independent spirit. And that brings us to his last name, Soofi.

I love the Sufi shrine in Delhi of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, a 14-century saint. I feel at home when I lounge in its courtyard.

For Mayank Austen Soofi is street-spiritual as well as funny, engaging and wise. Kate Kellaway

Mayank Austen Soofi will appear in an exhibition curated by the artist Subodh Gupta, featuring 10 artists from across the world, as part of the Serendipity Arts Festival, 15-22 December, Panaji, Goa

Nathaniel Grann, chosen by Alec Soth

Pop culture hasnt traditionally been kind to the American midwest. Lacking the romantic grit of New York and the light-dappled glamour of Los Angeles, the vast expanse of country from Ohio to Nebraska often gets a raw deal, lumped together as a homogenous bloc of flyover states synonymous with rural conservatism and Roseanne Barr.

There are a lot of preconceptions about the midwest, says Nathaniel Grann, which is crazy because its so huge. The 28-year-old photographer grew up in the middle of nowhere in Minnesota and his beautifully understated photography project Midwest Sentimental serves as both an exploration of the notion of family quiet domestic dramas, compelling portraits of his own parents and an affirmation of what that means in small-town America.

Ive always been fascinated by folklore, says Grann, going on to explain the appeal of Minnesotas folk hero lumberjack Paul Bunyan as analogous to his own work. Even though it ends up being a myth, its also very much a type of self-fulfilling prophesy.

In the case of Midwest Sentimental, which Grann shot on film over three years, nostalgia creeps through in both the set-ups and the style: a cousins man cave accented with deer heads, a bulky TV flashing grey fuzz, Granns father snoozing on a velvet La-Z-Boy.

Alec Soth, the revered American photographer and fellow Minnesota native who made his name with his 2004 book Sleeping by the Mississippi, was drawn to Granns eye for subverting banal cliche and rendering it compelling, quiet its understated but it works hard. The pair met when Soth visited the University of Hartford in Connecticut, where Grann was studying, as a guest lecturer on the photography MFA. Soth, much like the late photojournalist Michel du Cille, who hired Grann as a picture editor when he was director of photography at the Washington Post, has been key to encouraging him to pursue his ambition.

I was lucky they told me to keep going despite the harsh environment for [aspiring] photographers trying to make a living. That Michel du Cille saw talent in me, even getting acknowledged by someone like him a Pulitzer winner and knowing he had my back was so great, particularly in those years after school, when youre figuring out the whole hustle.

Grann shot more than 6,500 photos for Midwestern Sentimental, of which 36 made the final edit for the book. My stepmom first taught me to use a camera when I was around nine, he says. She was a nature photographer; she got me interested and I would use her Nikon F4. In high school, Grann developed a thing about war photographers I very much had that activist notion of how photos can change the world but it was time studying at the Danish School of Media and Journalism in Aarhus that proved the real gamechanger for him.

I was studying as [an undergraduate] at the Corcoran College of Arts & Design in [Washington] DC and had learned a lot of different ways to tell a story, but Danish photographers take a different approach to journalism and documentary photography and it allowed me to really try out new things and not be limited.

The Danish experience inspired him to slow down, which became essential to the tone and a lot of the self-reflection that came from spending three years observing and shooting his own family.

One of my approaches was staged portraits, which, clearly, are give-and-take situations with family members. Patience and understanding were needed on both sides of the camera to make his images work. I have a very early memory of my mother in a fur coat and of her carrying me in it through the snow, but my take on that coat was completely different from my mothers. She remembered it as a leftover from the end of her divorce.

Granns parents both remarried and the elements of his blended families have become central to his work. Eighteen months ago, he moved to Los Angeles and has been working in the day as a picture editor. I always joked the project would only come to an end when I moved out of my moms basement, he laughs. But there is something to be said about the perpetual summer of California. Nosheen Iqbal

Phoebe Kiely, chosen by Vanessa Winship

Phoebe Kiely is at a weird crossroads in her life. The 27-year-old photographer from rural Lincolnshire quit her retail job in Manchester in June, moved away from the city and has since been travelling. During this time she has photographed Glasgow, Verona, Sicily (I wanted to be by the water), and is now stationed in Budapest until the end of the year, where she is relishing the citys green spaces and pastel colours.

Before this odyssey, Kielys subjects were rather more monochrome: her first book, They Were My Landscape, published in May by MACK, is a collection of elegiac black-and-white photographs, named after a quote in Sylvia Plaths The Bell Jar. They capture a range of urban scenes a young man smoking at a bus stop, cracked concrete walls, a decomposing pigeon alongside more lyrical compositions: a delicate swan; the seas gleaming waves; a silver birch tree emerging from the darkness. The thread running through these images is Kielys eye for chiaroscuro, which imbues the images with contrast and drama.

Its all very instinctual, she says. Something aligns whether its light, shade, pitch. If I walk down a street today and the sun is incredibly bright, there are certain images Id take, and on a gloomy day, if I walk down the same street, Id probably take completely different images, but they would still be, hopefully, as valid as each other. So far her eye has served her well: Kiely graduated from Manchester School of Art in 2015, and in quick succession was exhibited at Liverpools Open Eye gallery, included in the British Journal of Photographys 2016 Portrait of Britain exhibition and nominated for MACKs First Book award.

Kiely was 14 when she got her first camera, a cheap digital device from Aldi, and although she never considered photography as a career I didnt know it could be, I didnt really know any photographers taking photos became a compulsion. While staying at her parents this summer she found an old diary where she had written about wanting to exhibit her work at the village gallery. Id never even been to a photography show at that point, she says, but I knew that was the dream, to have a show, which would have been atrocious probably. But its something thats embedded in me. Photography is the first thing I think of when I wake up; its the last thing I think of. It sounds terrible its doomed all my previous relationships. Its all-consuming.

For this feature, the acclaimed British documentary photographer Vanessa Winship who won the 2011 Henri Cartier-Bresson award and had her first major UK show this summer at Londons Barbican Art Gallery singled out Kiely for the beauty and simplicity of her work. It feels thoughtful, and we need thoughtful work, says Winship. It doesnt feel like its following a trend. Its work that asks questions, I believe, about who we are, who she is. It describes a state of being which feels very relevant in Britain today: a quiet disquiet. Another thing that attracted Winship to Kielys work was that, when she saw a few of her photos in a studio, she recognised them straight away as prints developed in a darkroom.